Musical beds

The latest report of the Public Accounts Committee on NHS Continuing Healthcare (CHC) in England[1] is to be welcomed – introducing, as it does, a note of reality to the discussion concerning the NHS’s responsibilities for people with continuing healthcare needs. The problem is not the growth in the numbers of people becoming eligible for such support (which is a mirage – see below) but that funding for it, is so difficult to obtain – as the Committee notes:

too often people’s care is compromised because no one makes them aware of the funding available, or helps them to navigate the hugely complicated process for accessing funding.

The committee points to chronic delays,[2] an ‘unacceptable variation between areas in the number of people eligible for CHC funding[3] and expresses the opinion that neither the Department of Health nor NHS England are ‘doing enough to ensure CCGs are meeting their responsibilities’. The committee also doubts that the CHC ‘efficiency savings’ that NHS England wants CCGs to make (£855 million by 2020−21) can be achieved ‘without increasing the threshold of those assessed as eligible, or by limiting the care packages available, both of which will ultimately put patient safety at risk’.

CHC numbers

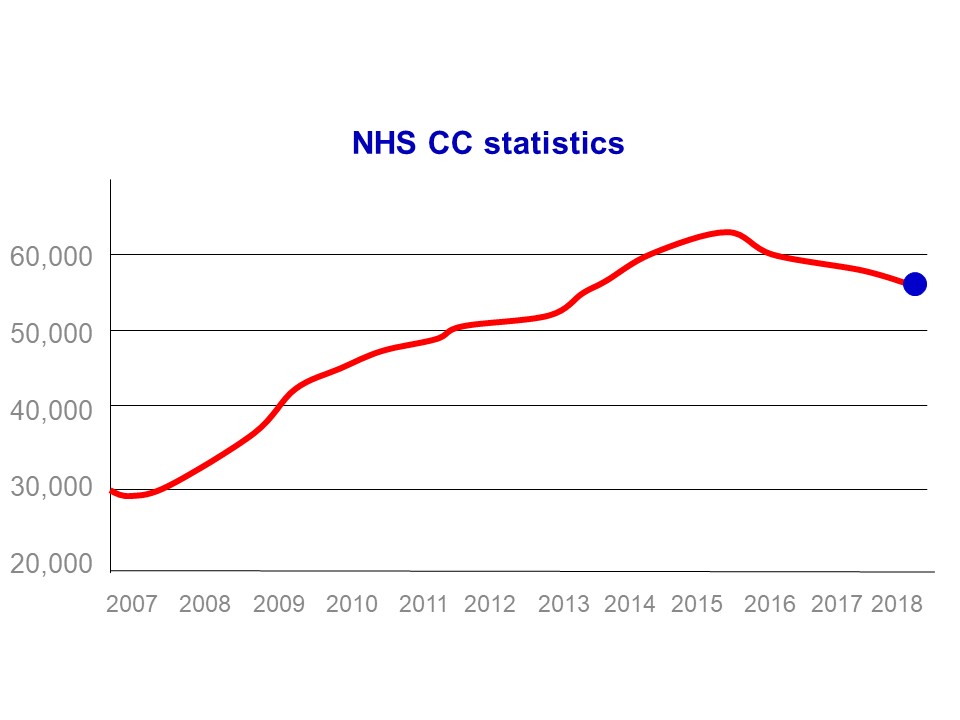

On micro level the statistics suggest that the number of people receiving CHC funding has increased (an increase of 26,000 since the Framework guidance was published a decade ago – see fig 1). That was certainly the stated intention of the 2007 reforms[4] which demanded a cultural change from health and social services[5] – and in any event an increase would have been expected due to England’s changing ‘age profile’: as a nation we are getting older and we are not getting any healthier.

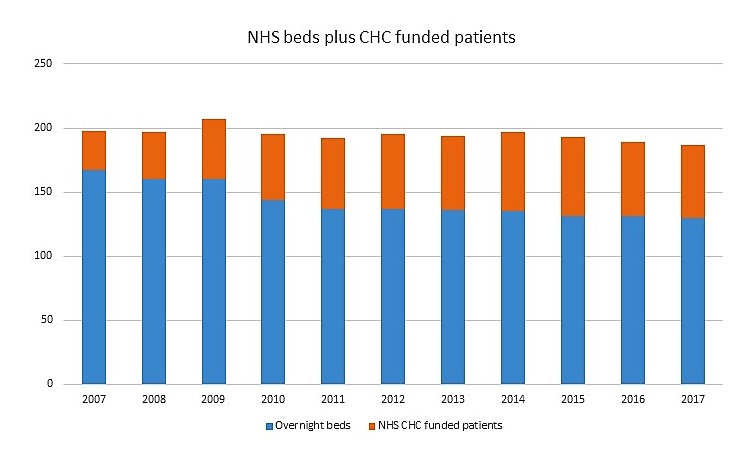

If however you look at the wider picture, it is clear that this change has not occurred. In 2007 the NHS in England had 167,000 overnight beds, whereas today it has 128,000:[6] a loss of 39,000 beds.[7] This means (even if we add in the increased number of CHC funded patients) the NHS is providing continuing care funding for 13,000 fewer people than it did 10 years ago – we are in fact going backwards (see fig 2).

This is the experience of many adult social services departments: that getting CHC has become more difficult to obtain. Indeed in some areas it is suggested that you have to be ‘virtually dead’ to get such support and this perception is also borne out by the most recent data. In 2017 of those in receipt of CHC funding, 30% received it under the fast track process – ie that they were terminally ill and likely to die in the near future.[8]

The latest batch of statistics also shows that the number of people receiving CHC funding has fallen by 5,000 in the last 2 years[9] (and during this period NHS overnight beds have been cut by over 2,500).[10] So this winter there are, on any one day, 7,500 chronically ill people being funded by social services or families who would have received their care from the NHS 2 years ago.

Another troubling trend, symptomatic of CCGs relentless pressure to cut CHC numbers (while simultaneously cutting NHS beds) is the way that many patients who receive CHC awards are then reviewed and held to be no longer entitled.

Reviewing and removing CHC patients

This trend was flagged up by a 2013 report which documented patients with progressive or ‘non-improving conditions’ (dementia, spinal cord injuries, profound learning disabilities etc.) who were either having their eligibility for CHC removed on reassessment or their care support ‘dramatically reduced after reassessments without there being any evidence of beneficial clinical improvement’.[11]

It is intellectually difficult to understand how someone whose dementia is so advanced that she is eligible for CHC funding and then (because the disease has progressed) ceases to be eligible. If she had a ‘primary healthcare need’ to become eligible – it is logically challenging to grasp how she can then cease to have a ‘primary healthcare need’. In this context an initiative by the Continuing Healthcare Alliance deserves support: their impressively reasoned proposal is that where a patient challenges the termination of their package the CCG should remain responsible for its funding until the Local Resolution Process has been completed.

As children, many of us played the harmless game of musical chairs. You danced and when the music stopped you had to find a chair to sit on. Those who failed to were no longer in the game. When the music started, a few more chairs were removed and when it stopped, more players had nowhere to sit and were no longer in the game. In the end there was only one chair.

The ‘game’ CCGs are requiring patients to play is one with beds not chairs. If the loss of NHS overnight beds continues, as it has over the last 35 years, we are on course to end up with only one. In it will be a patient who will be referred to as a ‘bed-blocker’ and the finger of blame will be pointed at wicked social services (and wicked families) for not discharging this person so that those ‘noble honourable dying people’ in the queue will have a chance to occupy it.

Unlike musical chairs this is not a harmless game – it is a ruthless and deadly game, and it has to stop.

Endnotes

[1] Committee of Public Accounts NHS continuing healthcare funding HC 455 (House of Commons 17 January 2018) See also National Audit Office Investigation into NHS continuing healthcare funding HC 239 Session 2017–2019 (NAO 2017)

[2] ‘About one-third of assessments in 2015−16 took longer than 28 days. In some cases people have died whilst waiting for a decision’.

[3] Ranging from 28 to 356 people per 50,000 population.

[4] The Department of Health ‘Resource pack: Introduction Module 1: slide 7 (2007)’ stated ‘we do expect there to be more people eligible for full funding’.

[5] Ibid ‘the Framework … is a change in system that will require PCTs and LAs to think and act differently’.

[6] See Statistical Press Notice, Quarter 2 2017-18 – NHS England – there being 127,614 beds at September 2017.

[7] See for example NHS England Bed Availability and Occupancy Data – Overnight ( KH03) NHS organisations in England, Quarter 2, 2017-18 (XLS, 146KB); Beds Time-series 2010-11 onwards (XLS, 85KB); and Beds Time Series – 1987-88 to 2009-10 (XLS, 34K).

[8] NHS England NHS Continuing Healthcare and NHS- funded Nursing Care Report Quarter 2 Report, England 2017-18 Dec 2017 – the total number of people eligible for NHS CHC was 57,153 as at the last day of Q2 2017/18. Of these, 39,906 were eligible for Standard NHS CHC and 17,247 were eligible for Fast Track NHS CHC.

[9] NHS England NHS Continuing Healthcare and NHS- funded Nursing Care Report Quarter 2 Report, England 2017-18 Dec 2017 – the total number of people eligible for NHS CHC was 57,153 as at the last day of Q2 2017/18. Of these, 39,906 were eligible for Standard NHS CHC and 17,247 were eligible for Fast Track NHS CHC.

[10] NHS England Bed Availability and Occupancy Data – Overnight ( KH03) NHS organisations in England, Quarter 2, 2017-18 (XLS, 146KB) from130,169 to 127,614.

[11] All Party Parliamentary Group on Parkinson, Failing to care: NHS continuing care in England (2013) p22.

Posted 21 January 2018